Wait, what? What is this doing here? The Commodore 64 is as American as apple pie, right? This is a Japanese Vintage Computer Collection blog, no? Commodore has a lesser-known side to it – Commodore Japan.

Actually, this is by far the rarest piece in my collection. I struggle to find exact numbers, but I have only seen this item appear on Yahoo Auctions four times since I started paying attention about three years ago. By contrast, I’ve seen probably 100 MAX Machines in that time, which themselves are considered quite rare.

From a distance, it looks like a standard Commodore 64. In fact, the product name is just that: Commodore 64. But this is the Japanese edition. What’s the difference? Well, in some ways they are very similar, but in other ways, they are night-and-day different.

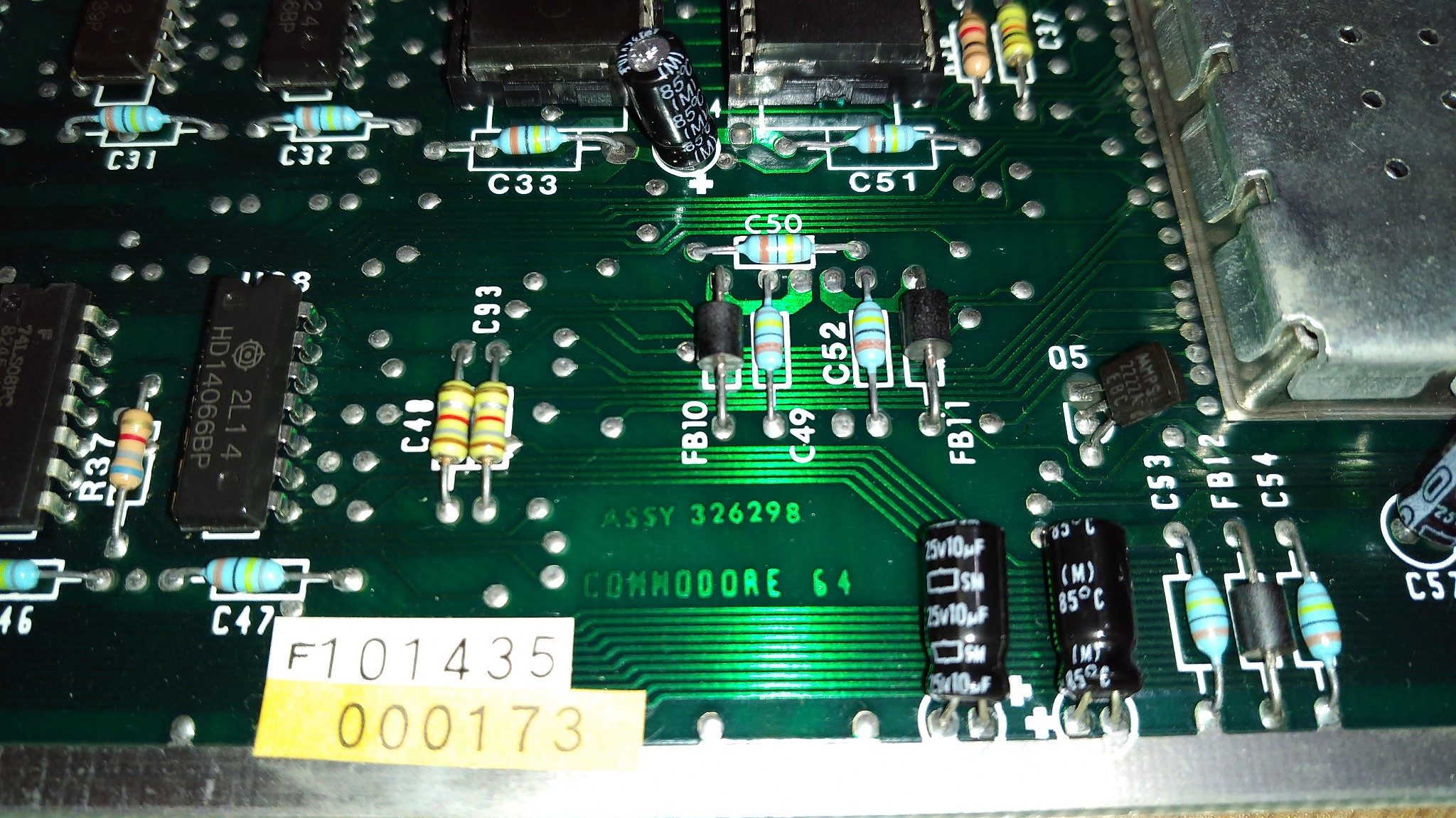

If you crack open (not literally!) the machine, you’d think you’re looking at a regular Commodore 64. Don’t think there’s any component in here that you couldn’t find on a standard Commodore 64. CPU is the same, SID (6581) is the same, PLA is the same, VIC-II is the same, and I gather the smaller ICs are also the same. The contents of the character ROM and kernal ROM are different. We’ll look at how that pans out later.

Put the cover back on, and with a more careful look, some differences are apparent. Probably the most eye-catching thing initially is that the shift-lock key has been replaced with what we’ll call “C=-lock” (and verbalize as “commodore-lock”). Off in the opposite corner, the £ key has been replaced with the ¥ key. But take a look at those characters on the fronts of the key caps. On almost every key is a Japanese katakana character.

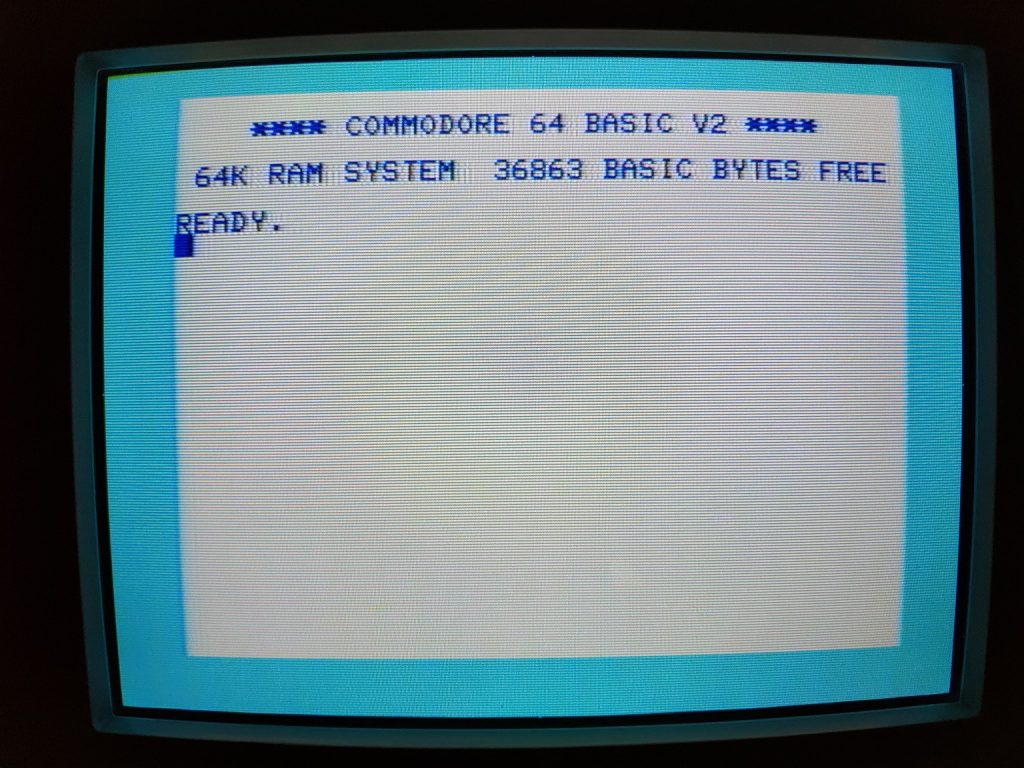

Before we start, we have to turn on the computer. And that’s when we see another set of differences: at the BASIC screen, the default color scheme is different, the font is different, and the amount of free memory is different (more on this later).

So let’s get to typing that katakana! When you type, though, the alphabet appears. How do you access the katakana? First, you must enter the second character mode, by pressing C= + shift (lowercase mode on a standard Commodore 64). After that, katakana is accessed the same way you access the petscii characters in the corresponding locations on a standard Commodore 64: by pressing C= and typing the characters. That’s why that C=-lock key is so useful!

The ¥ key produces the yen symbol without the need for the C= key. And although they are not visible on any key cap, there are also three kanji that the system can produce. They are directly accessible by pressing shift and typing the +, -, and ¥ keys. The characters are 年 (year), 月 (month), and 日 (day) All of the katakana and kanji characters are handled by a one-to-one replacement in the character ROM.

Katakana is usually used for writing or typing loan words from western countries, but it contains every sound of the Japanese language, meaning you could type an entire document or book with it. It would be a nightmare to try to read a large body of text that way, but it would be possible.

Compatibility with western software is varied. First, it’s NTSC only, so PAL games that don’t work on a North American Commodore 64 won’t work on this machine, either (although I feel PAL and NTSC incompatibility, while certainly extant, is overblown). Additionally, due to the character ROM difference, games that rely heavily on text may load but could be unplayable unless a custom character set is employed by the software. And most cracked software won’t work as-is because of the memory offset, although this can usually be easily worked around.

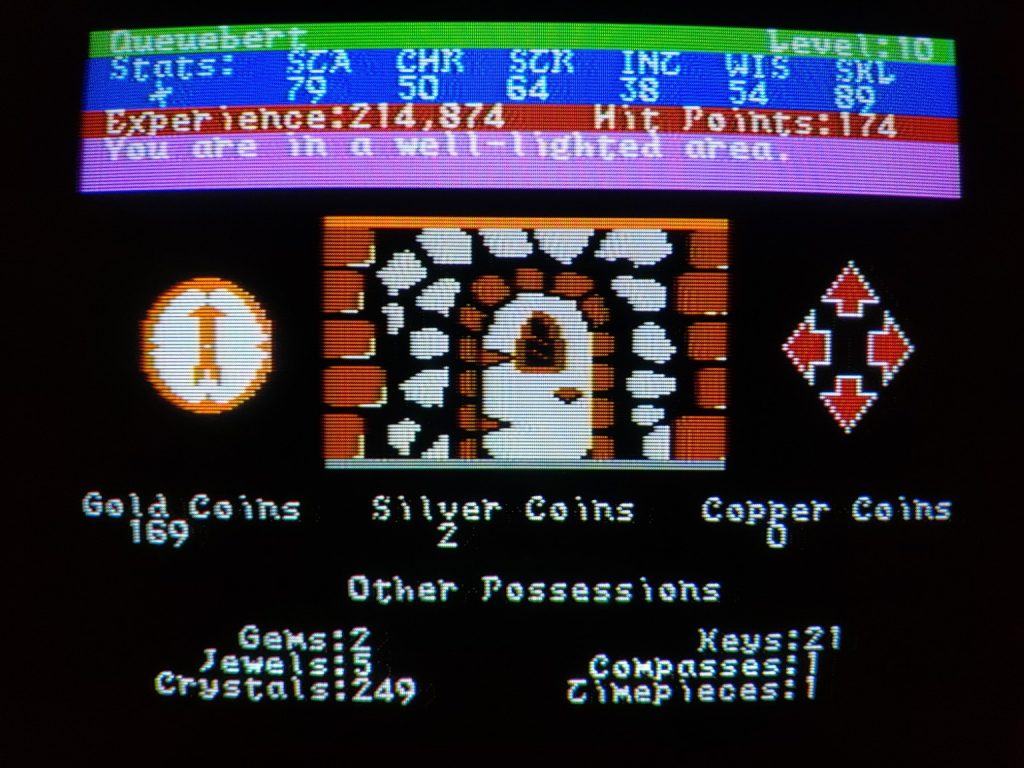

For the most part, though, I find original games load just fine. Here it is playing Alternate Reality: The Dungeon, my favorite game of the time.

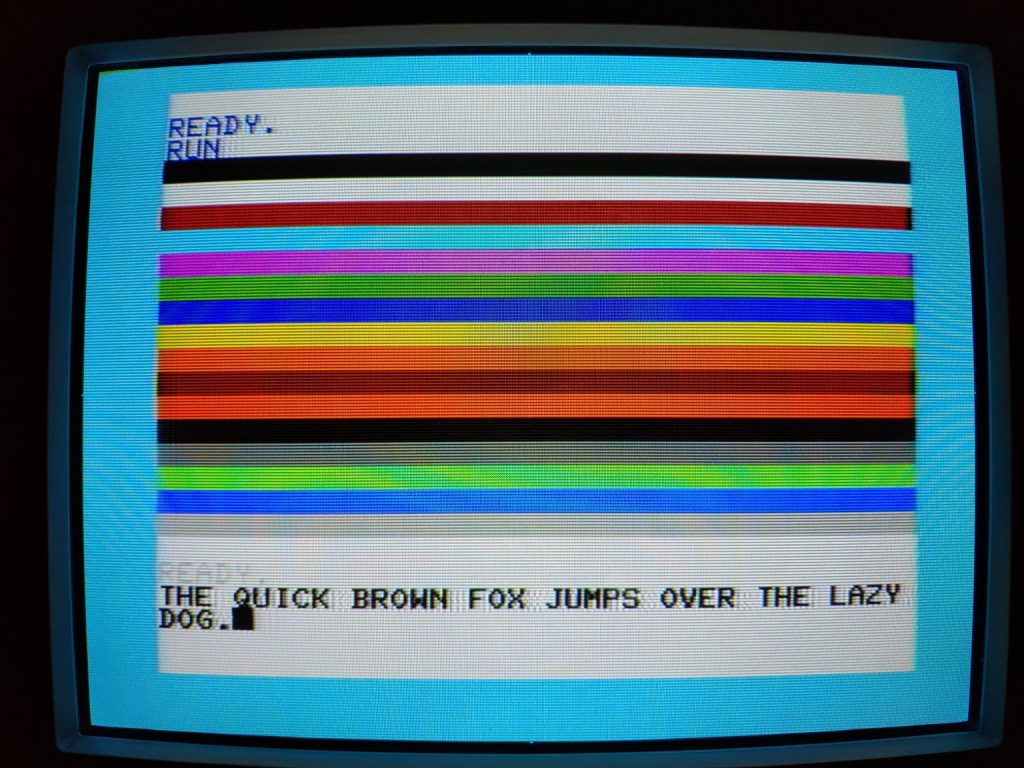

The first picture is a title screen and shows the kinds of problems that may occur due to the character ROM difference. Fortunately, that’s all sorted out before the actual game starts. The second picture is from the game’s introduction. This image made a big impression on me since the first time I loaded it, and it will stick with me forever – it shows just how beautiful and vibrant this 16-color computer is really capable of being. The third is an in-game shot.

There is another option for loading games. Fastload or replay cartridges such as Epyx Fastload or Action Replay can be plugged into the system. This forces the memory to be reconfigured to the expected amount available to BASIC. In the case of Epyx Fastload, this works as long as Epyx Fastload is capable of loading your desired software. In the case of Action Replay, you can disable the fastloader, the memory will still reconfigure, and then you should have the same compatibility as a North American Commodore 64 (possibly exempting character display problems).

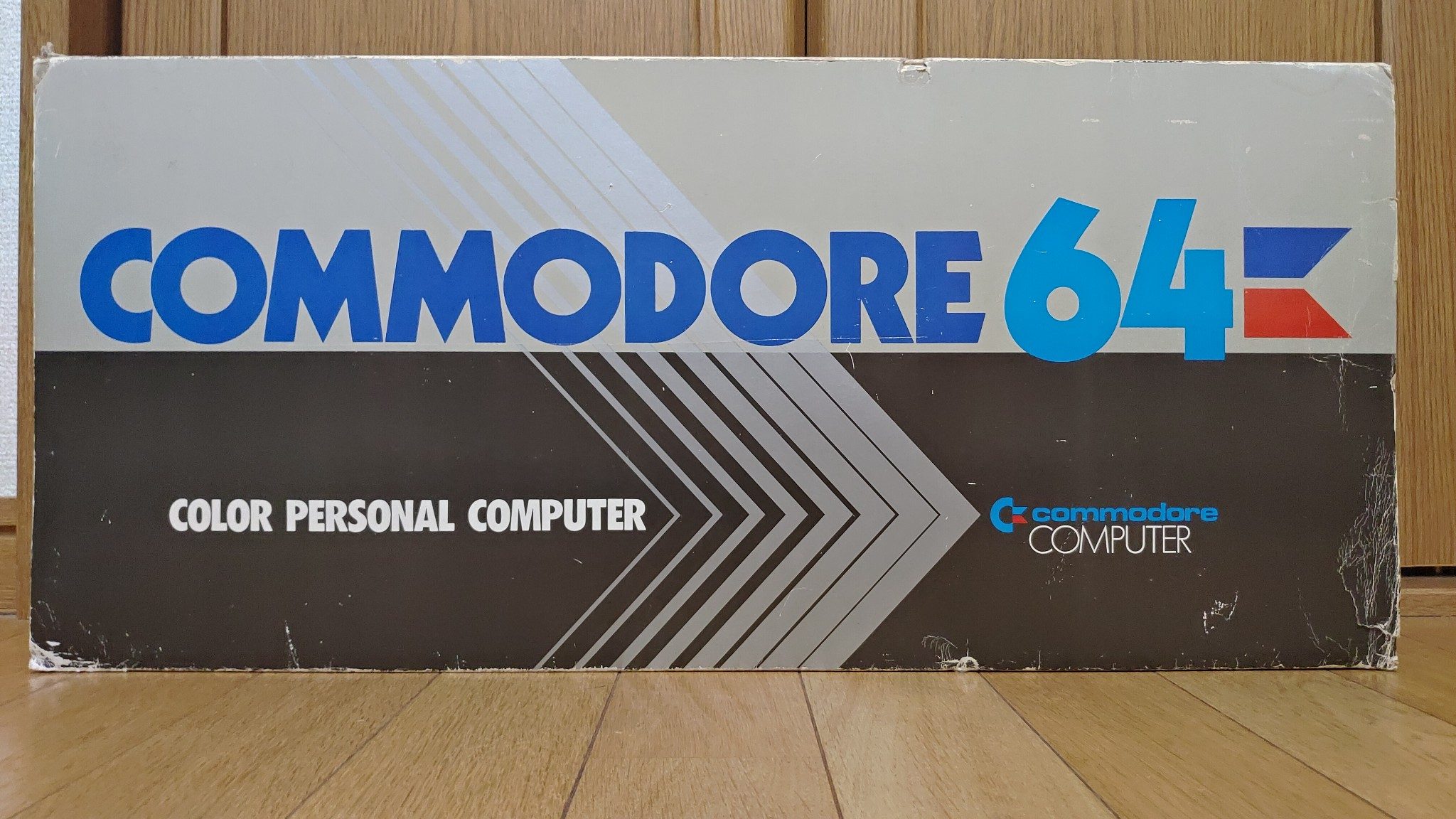

The box is also apparently unique. I’ve heard a couple of people who collect C64 boxes say they’d never seen this one before. It’s in a bit rough shape, but I think you can get the idea.

I just noticed but Sean, what board revision is this ????

Its very similar to the early vic 20’s where the power regulator is shielded in.

Hey Chris, good question. It’s a 326298, the first version, but there is one big difference between this and the US 326298. Instead of the 5-pin AV DIN which can only give out composite, it includes an 8-pin AV DIN like the later revisions, so it can produce separate chrome/luma signals.

An 8-pin Av DIN ??? I wonder why the U.S version didnt have it ?? Cost perhaps ?

Later versions had it! It was probably “enough” at the time, I suppose, but I’m not really sure. The chroma/luma separated output sure was a huge difference-maker for graphics, to be certain!

Where did you manage to pick this up? I’d be pretty tempted to buy it if I found one..

Hello, thanks for the comment! I got it on Yahoo Auctions. They’re really hard to come by, though. Haven’t seen one in maybe a year now. I was pretty lucky to get it, because even though it was probably my most expensive vintage computer, the Japanese C64 I saw before this went for almost twice the price and didn’t have a box!