Japan had its own computer revolution in the 80s that we might say paralleled that of the western world. It’s absolutely overwhelming at first to look through all the potential offerings. In the US, we had three big-time 8-bit players – Commodore, Atari, and Apple -and a host of manufacturers with smaller market shares. In Japan they also had three mighty participants – Fujitsu, NEC, and Sharp.

Sharp is a multi-faceted business, with two separate arms participating in the computer industry with their own 8- and 16-bit offerings. First was the Sharp MZ series from Sharp’s computer division, which contains many different models with a wide variety of often amazing aesthetics. And later, Sharp’s TV division would go on to release the highly-touted X68000 series.

What I want to talk about is a product that came out between those two ranges – the X1. It, too, was released by Sharp’s TV division, and the computer is indeed loosely integrated with TVs, although I find the computer itself far more interesting than its rudimentary TV interaction capability.

My particular model is the Sharp X1 Turbo Z. We can think of it as a third-generation model in Sharp’s nearly non-stop onslaught of new releases of the X1. It offered some major advantages over the original X1.

The original X1, which itself had many models, offered 8-color graphics on a high resolution screen (640×200) over digital RGB, but the X1 Turbo introduced 8-color 640×400 graphics over digital RGB, with the ability to display over both at the same time. The Turbo Z added analog RGB and also had lower resolution modes that allowed up to 4096 colors on the screen at once. That seems really impressive for an 8-bit machine!

The second big advantage that the X1 Turbo (and Turbo Z) had over the original X1 is the audio capabilities. I don’t know a lot about audio terminology, but I will explain as best I can. The original X1 used PSG technology for its audio, whereas the X1 Turbo introduced FM synthesis.

It is like night and day; you don’t need any sort of a finely tuned ear to catch the difference. PSG is perhaps a little more sophisticated than a IBM PC clone’s internal speaker. FM synthesis sounds closer to real musical instruments coming from your machine. The Turbo Z also kept this far more advanced audio technology.

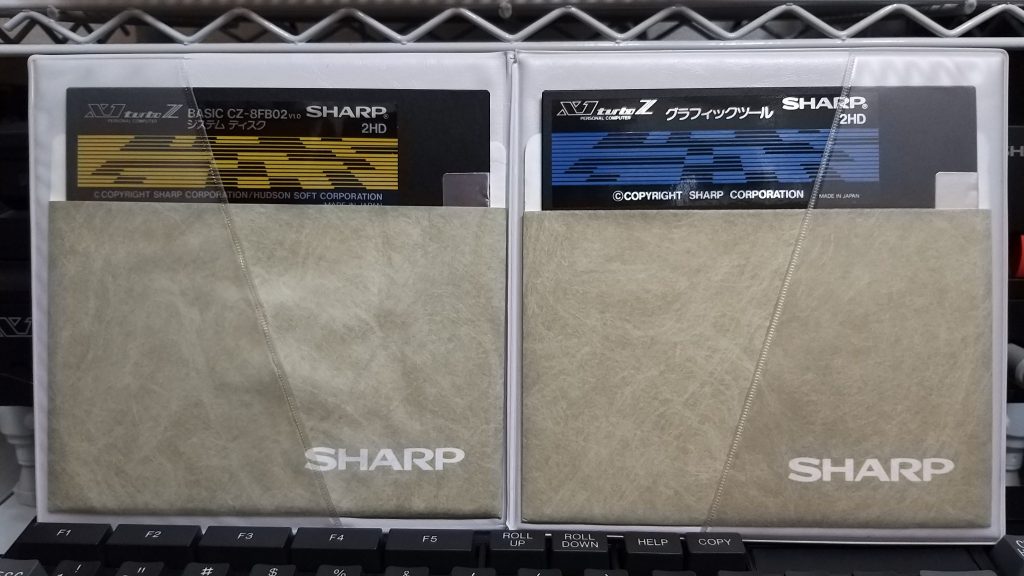

The third big advantage of the X1 Turbo Z is storage. The X1 and X1 Turbo had two base choices – tape drive or two double density floppy drives, with add-ons for either system to be able to use both storage technologies. The X1 Turbo Z introduced two high-density floppy drives. This approximately tripled the available capacity of the previous X1s and X1 Turbos that used floppy disks.

On the front of the X1 Turbo Z we find many switches and dials, which I think add a lot of charm to the computer but they have it all tucked away under a push-button drawer.

And they control a lot of important functions, here are the ones that may not be entirely self-explanatory:

– The third dial from the left is a PSG-FM mixer, which, depending on software, allows a sort of hardware-based balance between background music and sound effects.

– The red and white buttons are both reset. The red one will reset the computer entirely. The white one, again depending on software, may take you to the opening instructions of the software, or if it has no handler, will also completely reset the computer.

– The first black button switches between DD and HD mode (and LEDs change color based on mode! YAY LEDs!).

– The next black button is the VTR mode, which I am guessing allows it to interface with a VCR and launch a recording session.

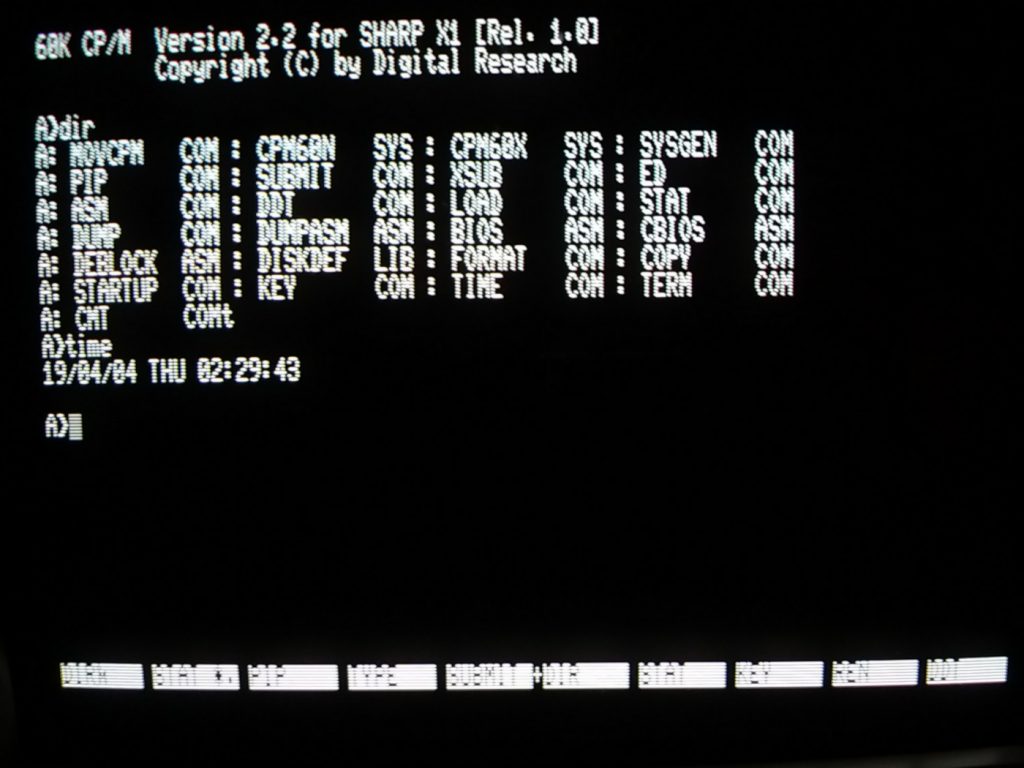

– The next two work in conjunction with one another, basically you want both to be “on” to enable and enforce high resolution mode. Some software can’t handle high resolution mode, though, so for example, CP/M should be booted in standard resolution.

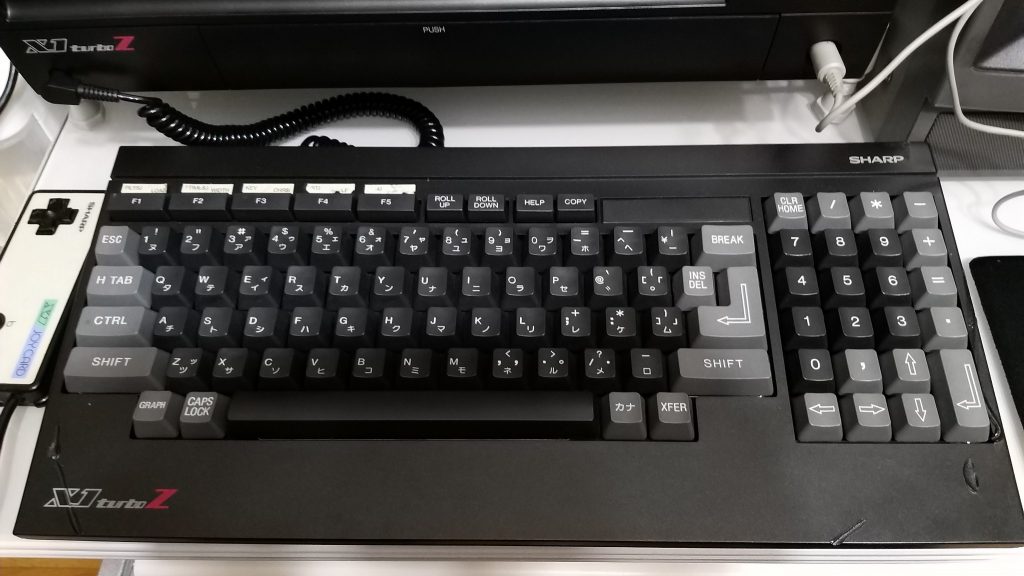

The X1 series has a distinct keyboard style, which didn’t change much between different X1 models. Mine also came with an X1-specific keyboard cover, kind of reminiscent of the covers I have for my Commodore computers.

On the back we can find a host of ports that are pretty typical for Japanese computers of the time. A couple of perhaps unexpected items are the video in/out ports for the “telopper”, which I believe allows for an overlay to the X1’s video output, and the TV-control, which allows for keyboard control of a monitor or TV that conforms to this standard.

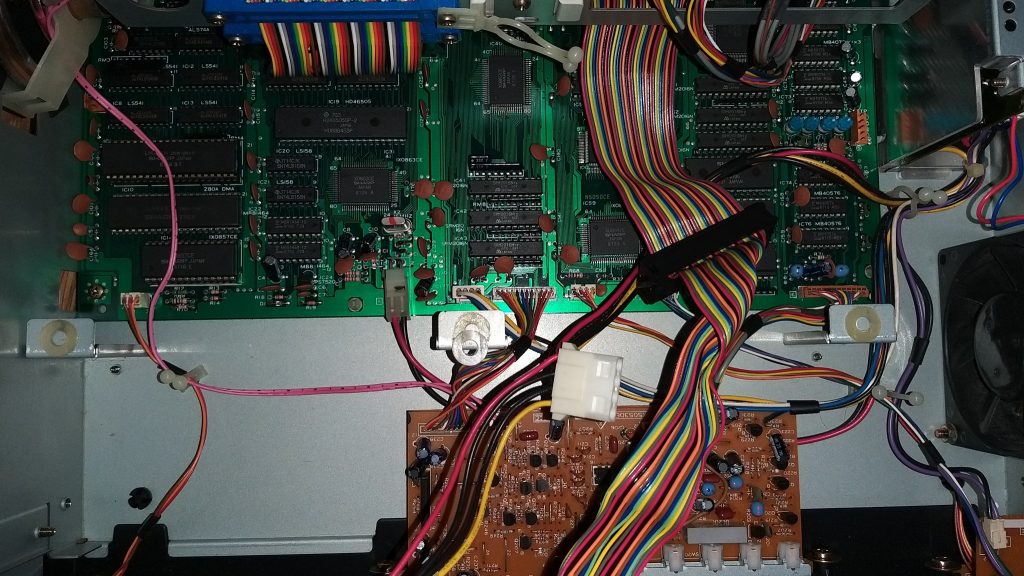

Inside, the computer is quite attractive, having a clean and well organized, not to mention somewhat colorful collection of boards and cables. With its expansion port capabilities, it looks a little more like a modern PC as we know them than the Commodore 8-bit line does.

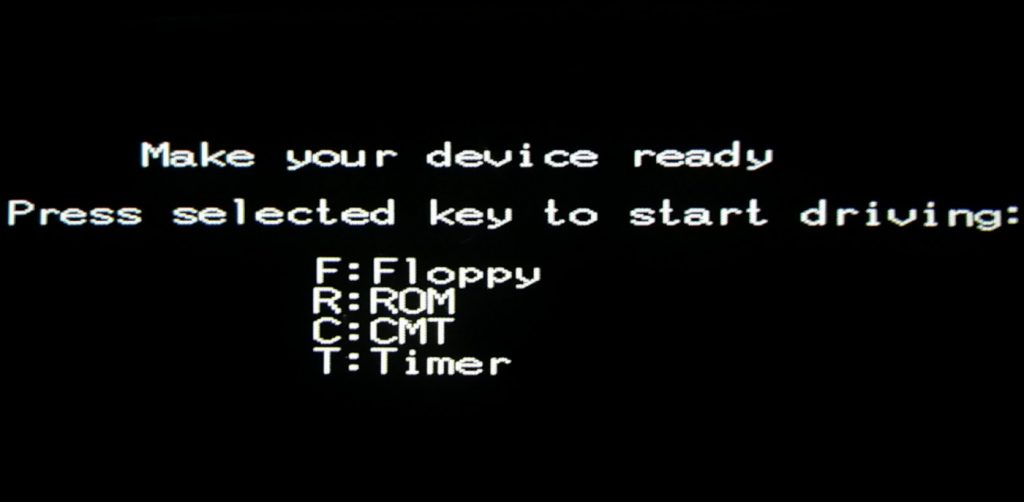

When you turn on the computer, you are greeted by this screen:

You can boot from floppy, access software stored on a ROM (there is no ROM-based software included), launch a program from cassette tape, or enter the timer.

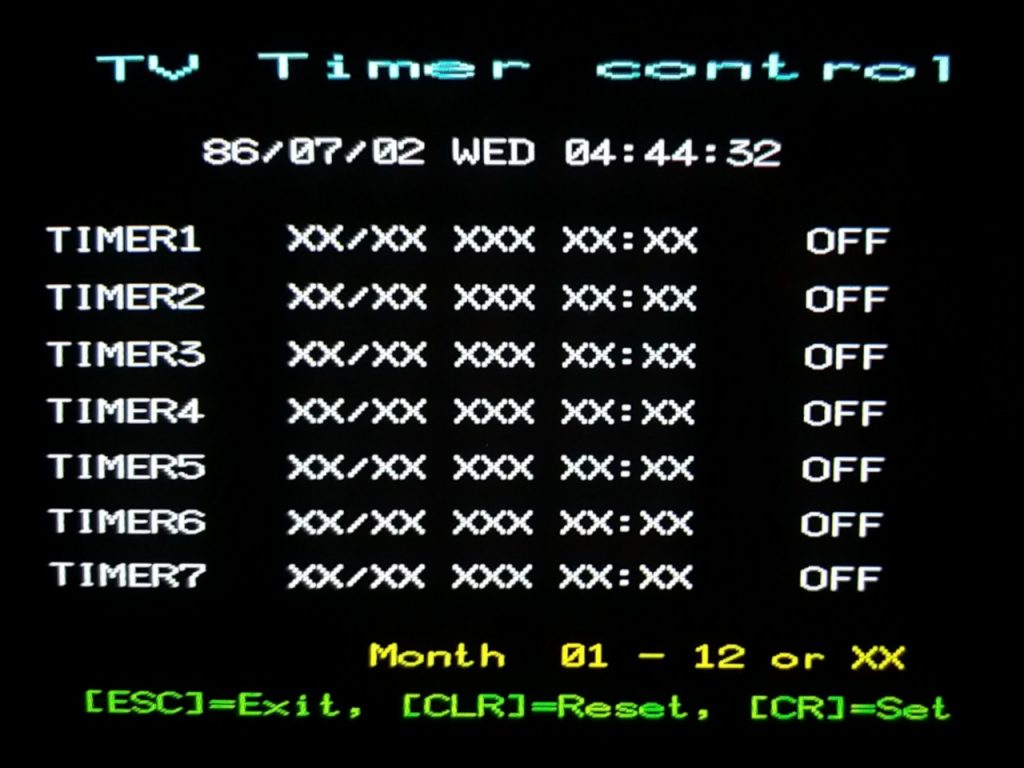

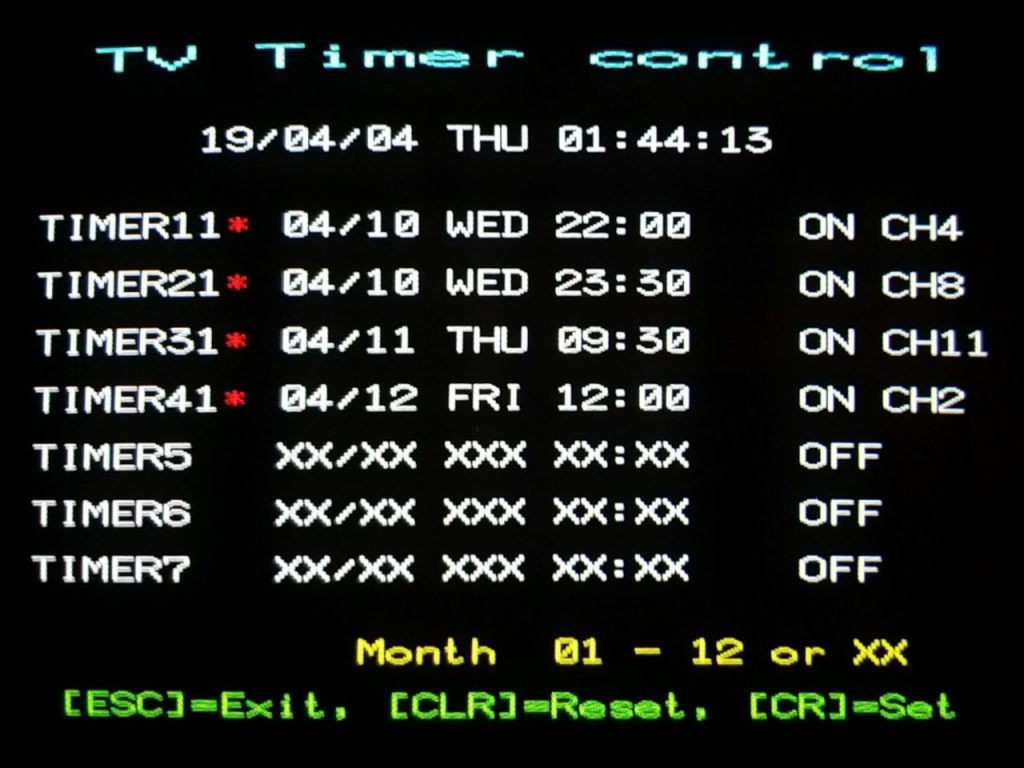

The timer is an interface to control when to turn on and off your TV and what channel to set it to. You can set up as many as seven timers, which are stored internally.

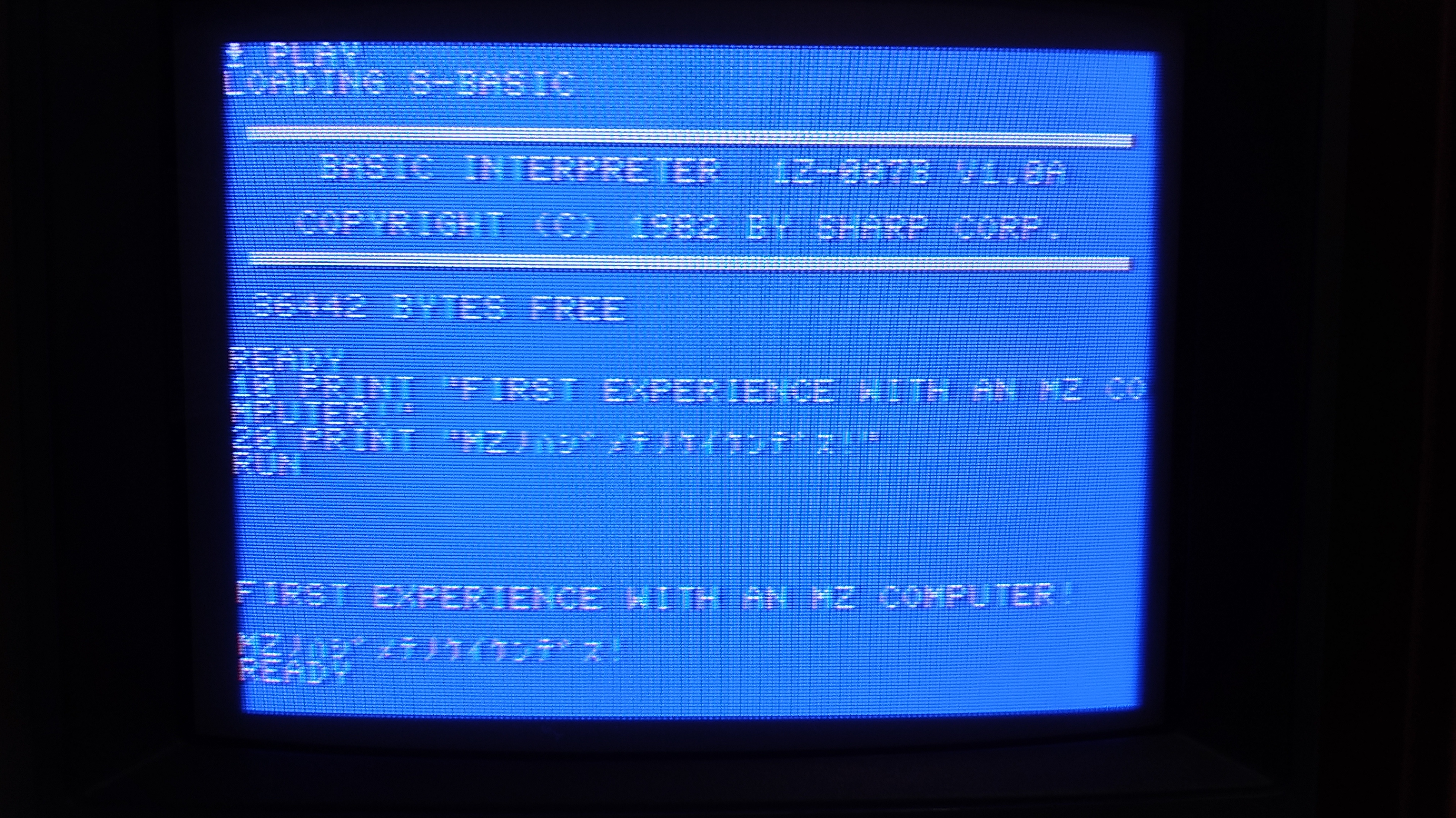

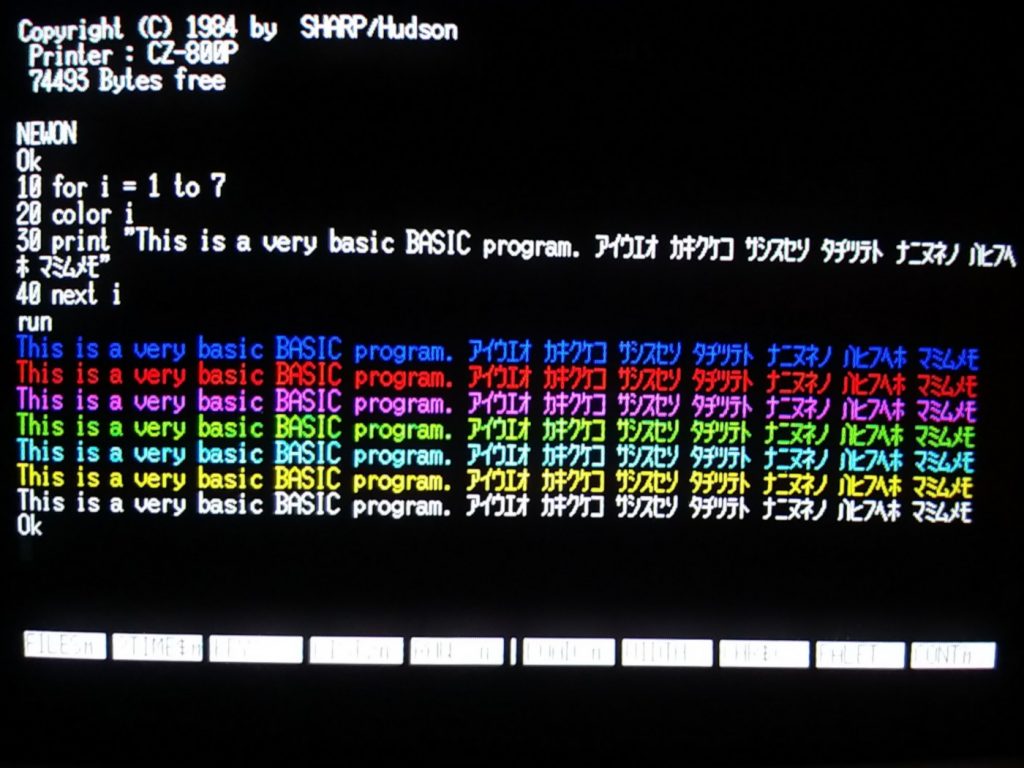

The system shipped with three programs, BASIC CZ-8FB02, Graphic Tool, and FM Synthesizer Music Tool. These are actually the names of the software packages, and each is on its own floppy disk. The disks are presented with snazzy-looking labels in a nice case. Here is also a very simple BASIC program that shows the machines vibrant colors (eight-color mode) and about half of the katakana character set.

Additionally, there is a version of CP/M available for the X1. It is not included with the system.

So what do the games look like? I actually don’t have too many available at the moment. I don’t have a floppy emulator, so I am relying on the few games I managed to pick up at a decent price. But here are some examples!

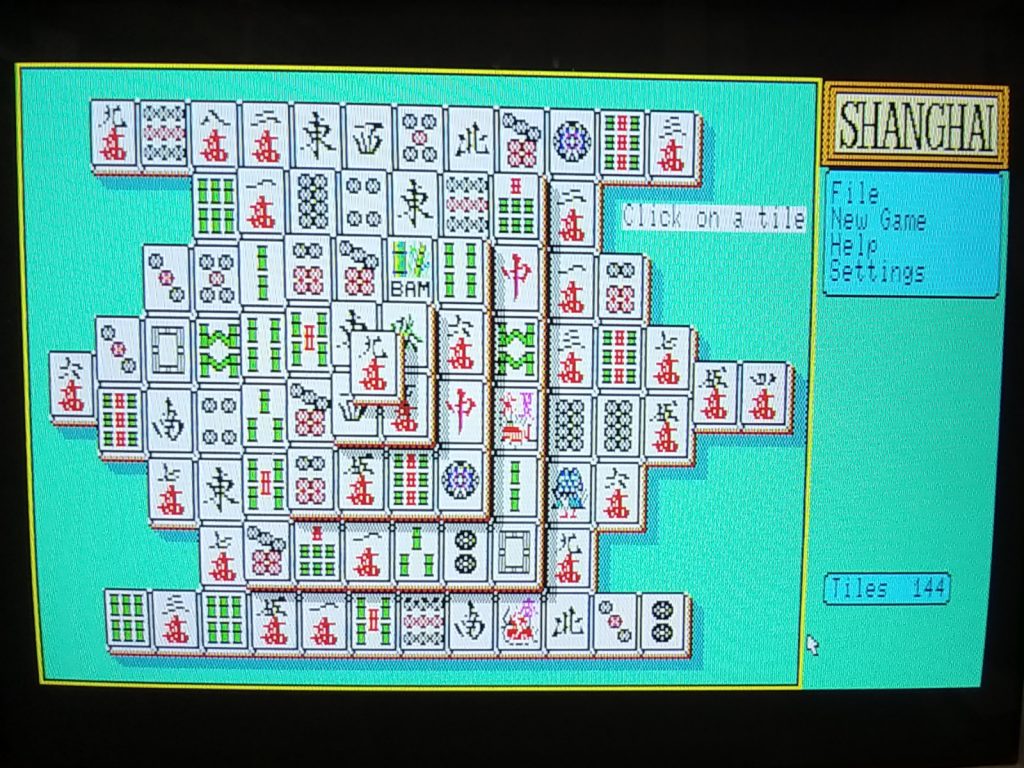

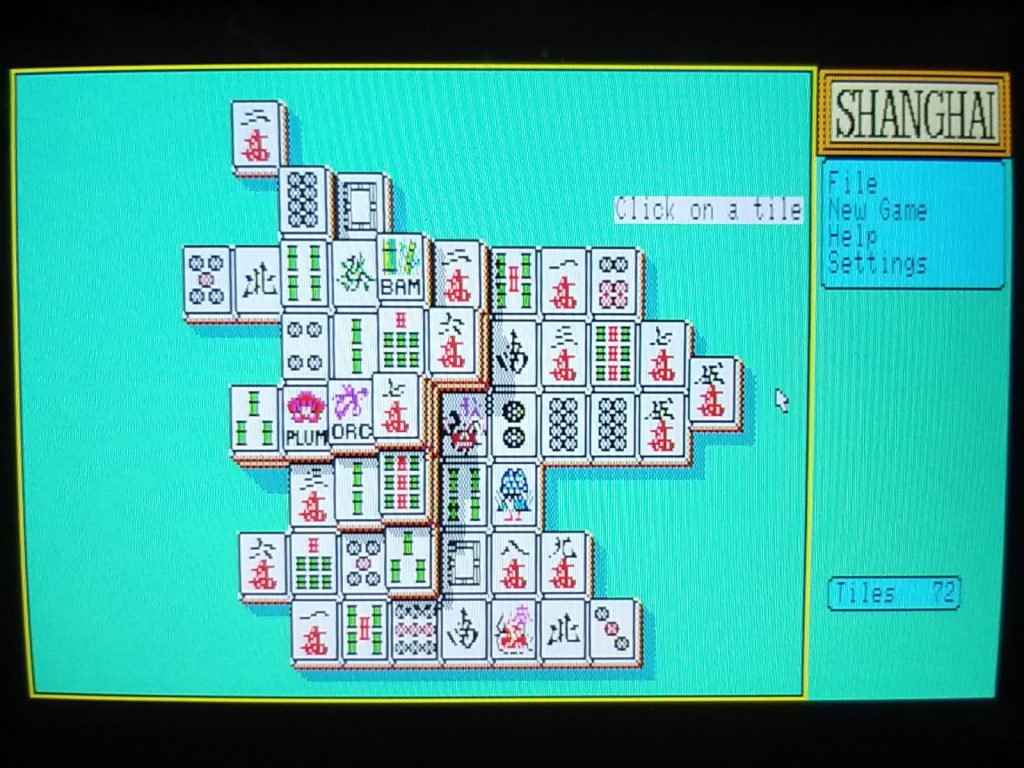

Shanghai (Mahjong):

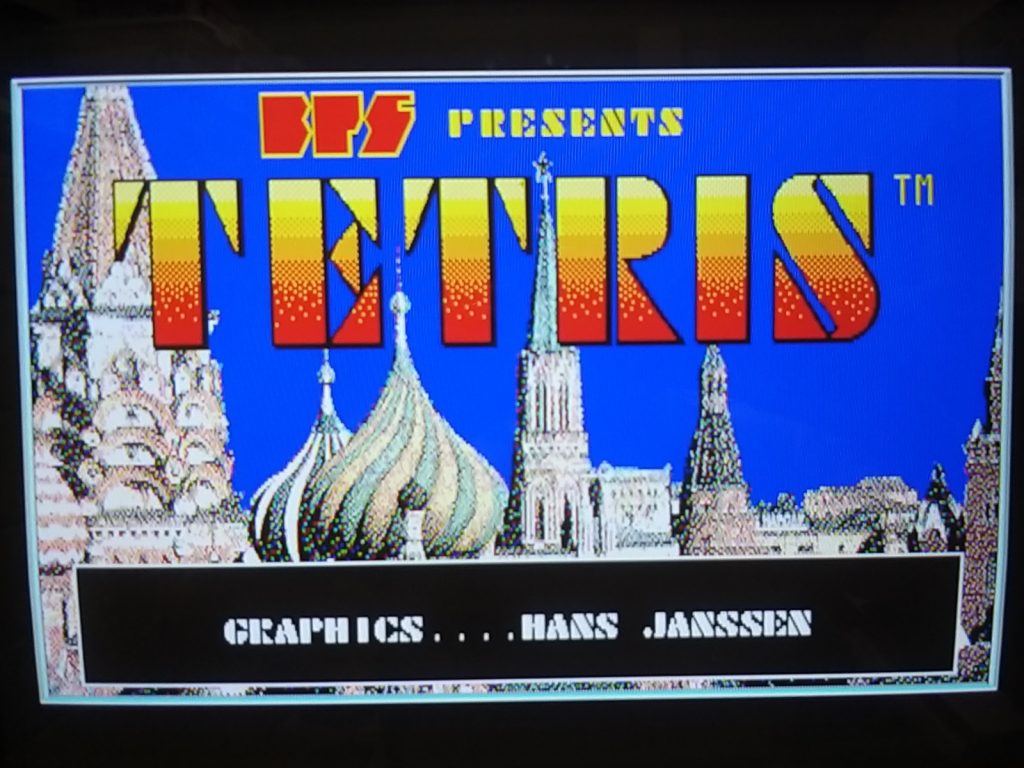

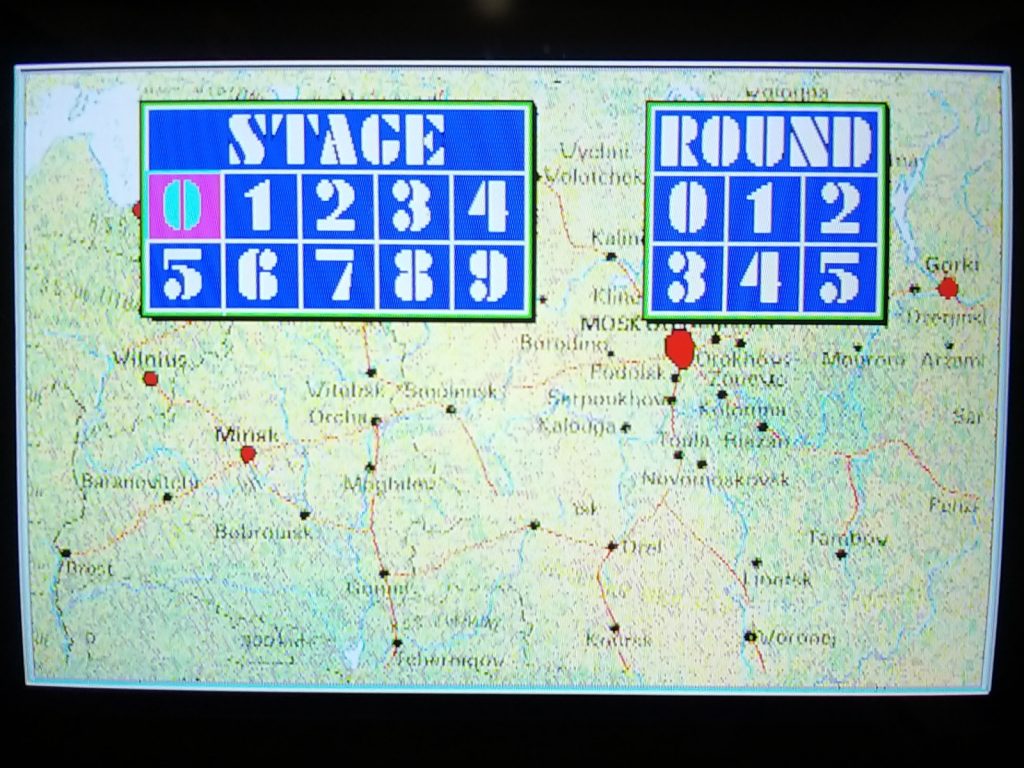

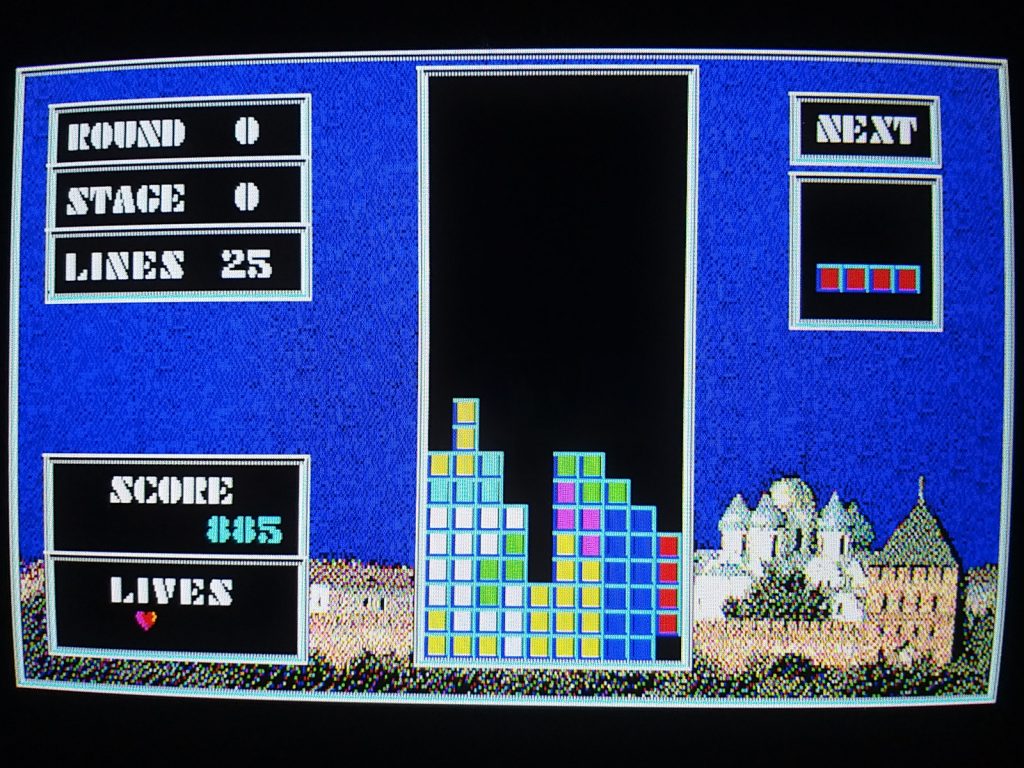

Tetris (duh):

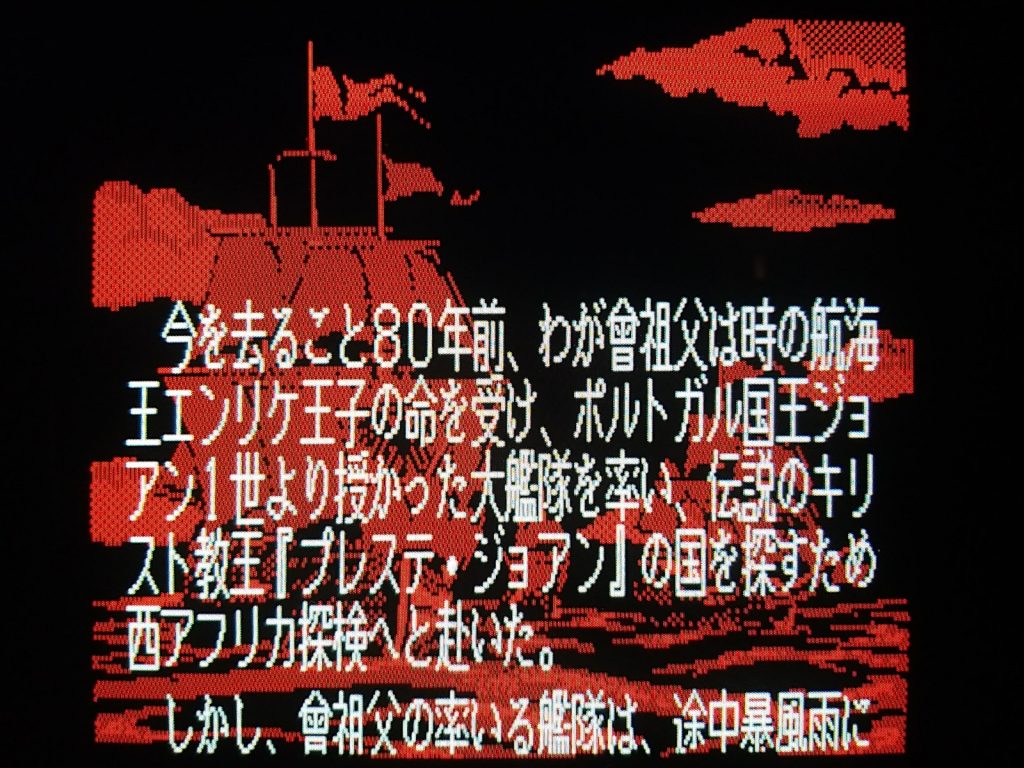

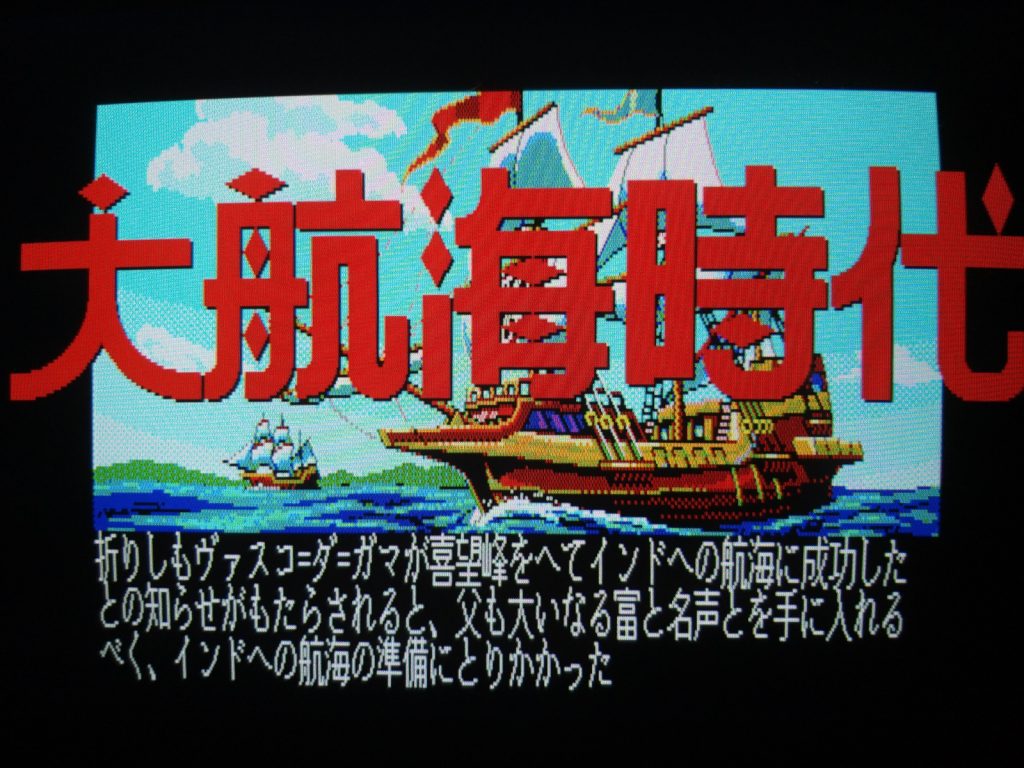

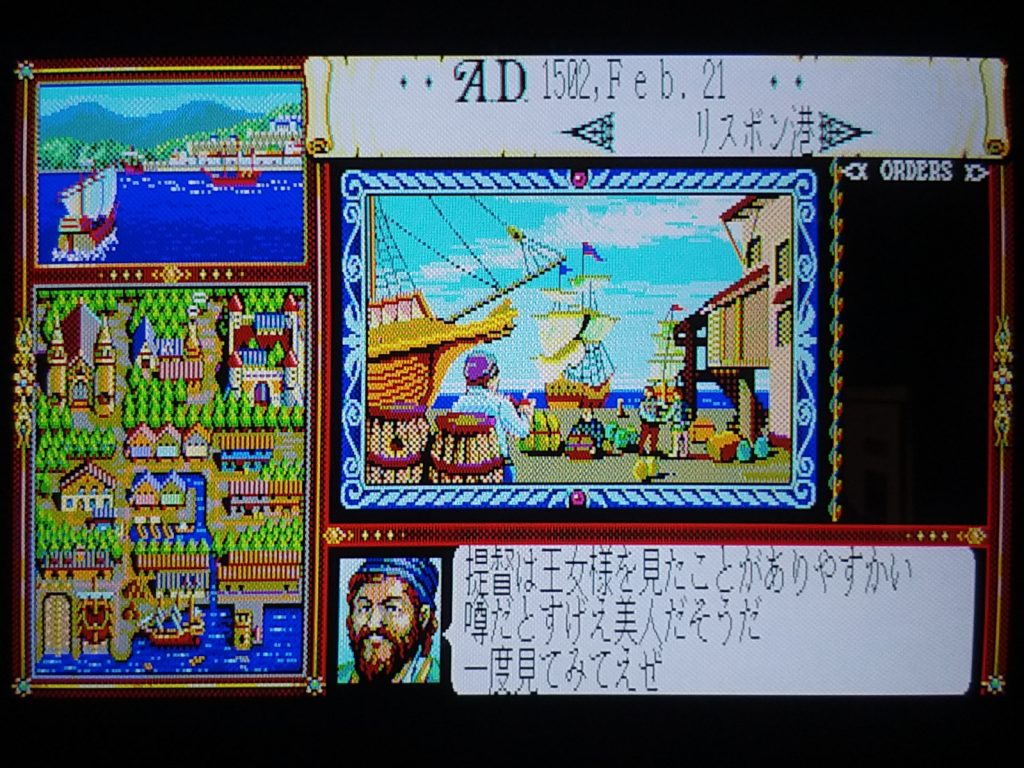

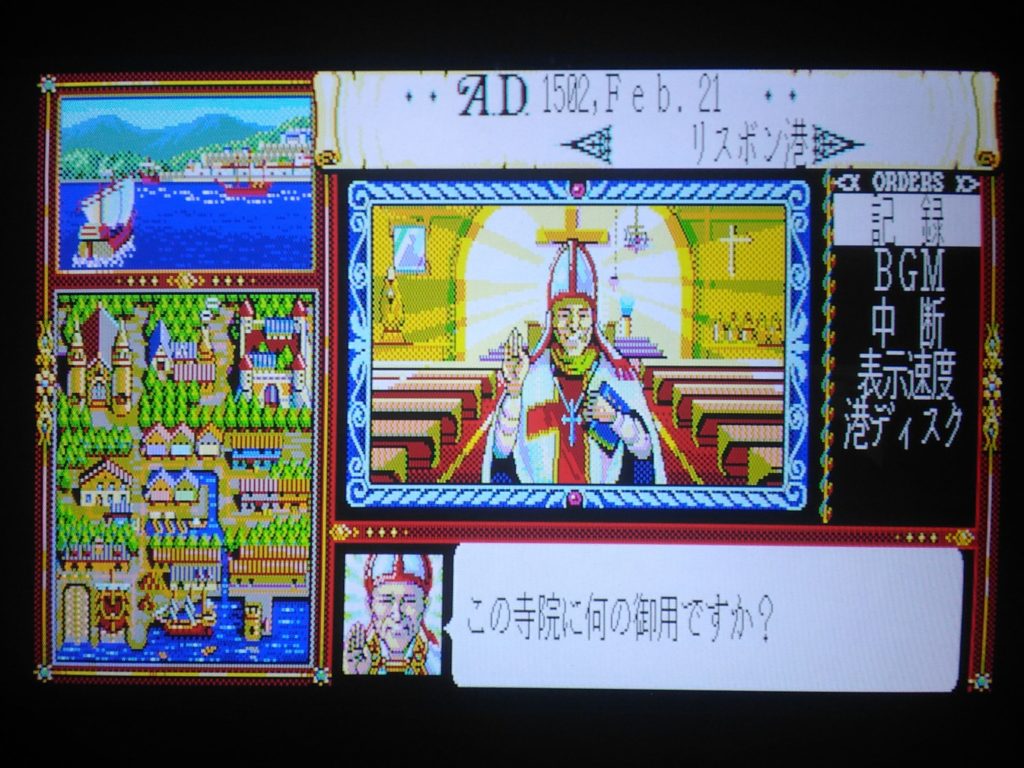

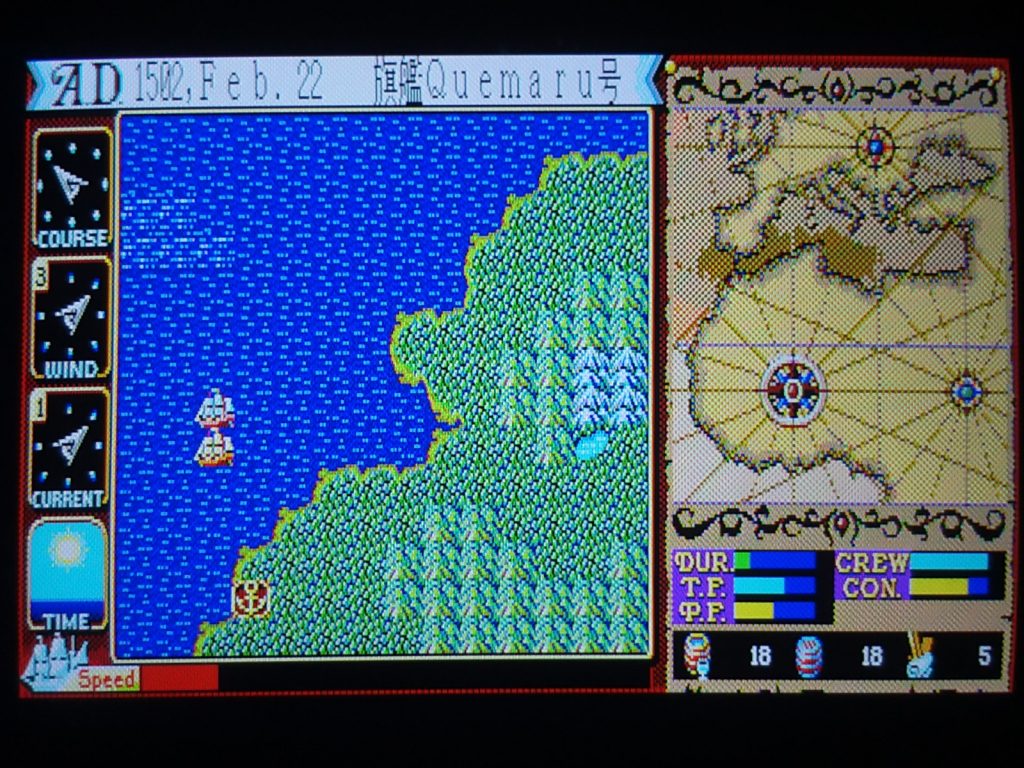

Daikokai Jidai (released in English as Uncharted Waters)

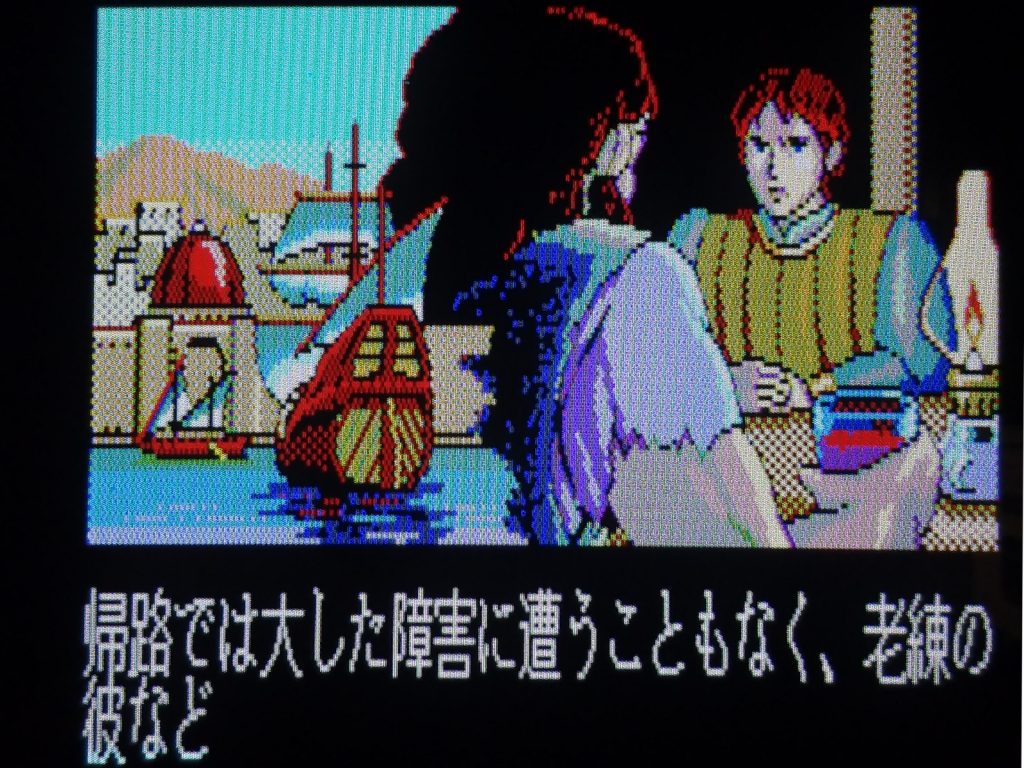

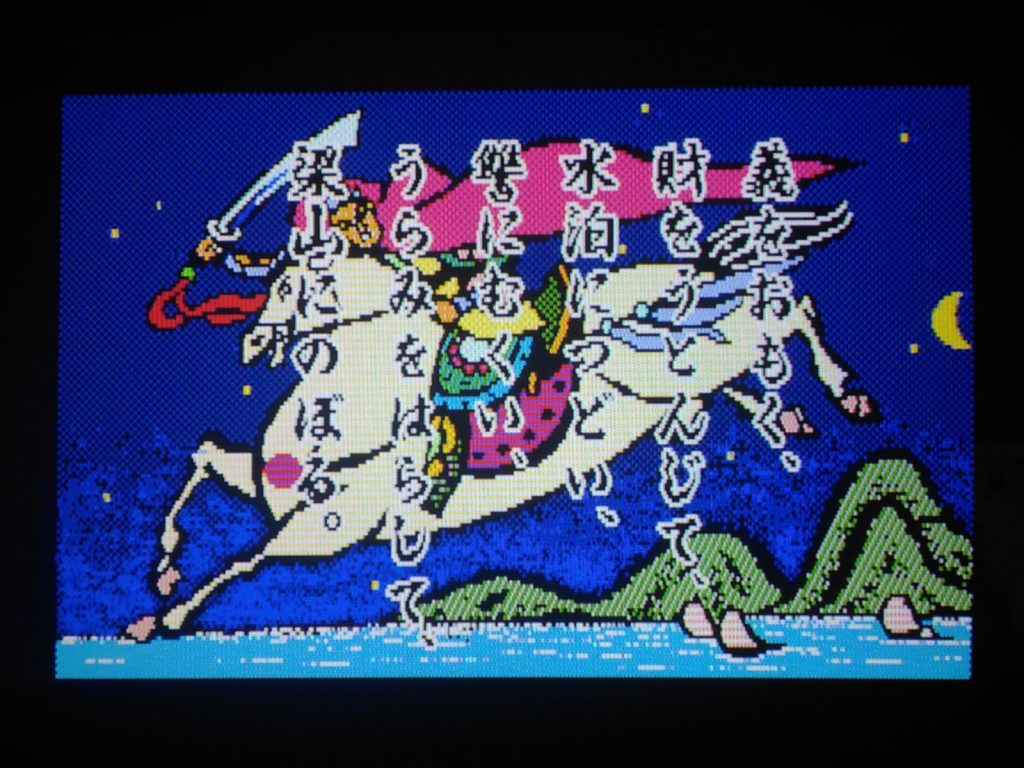

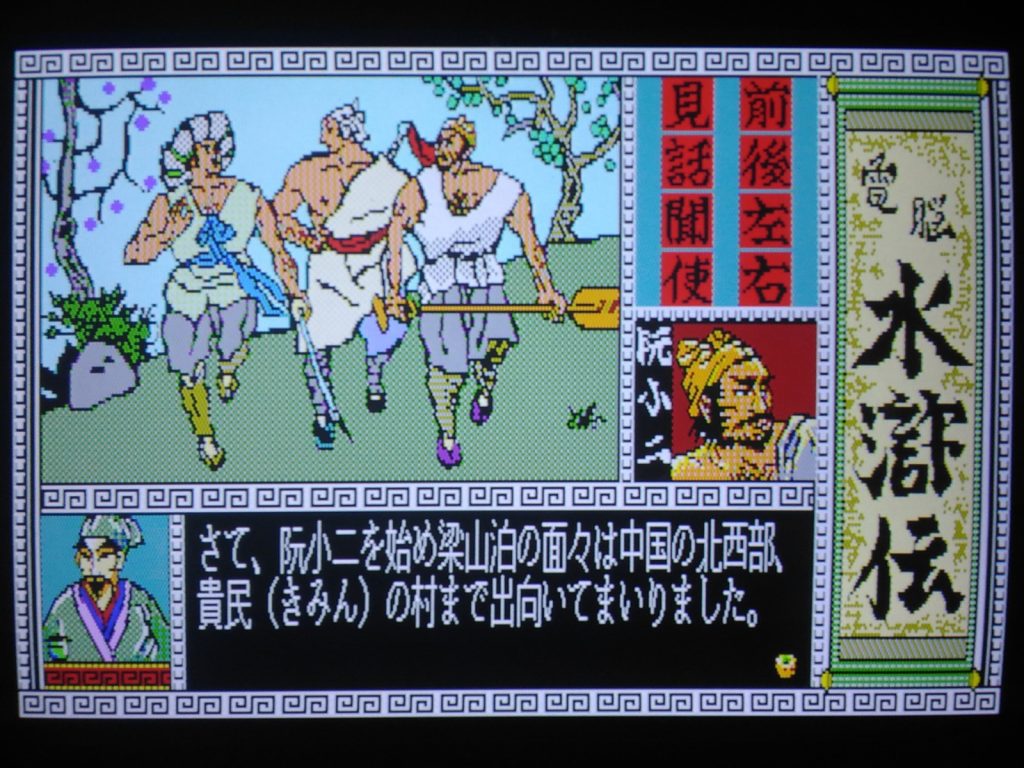

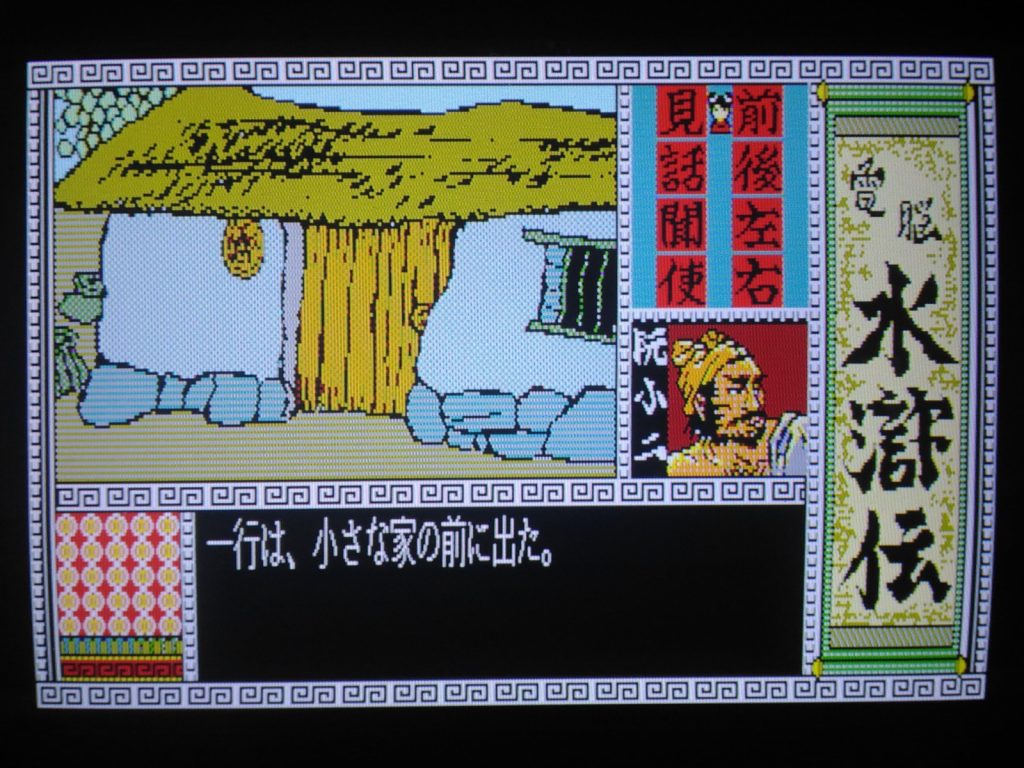

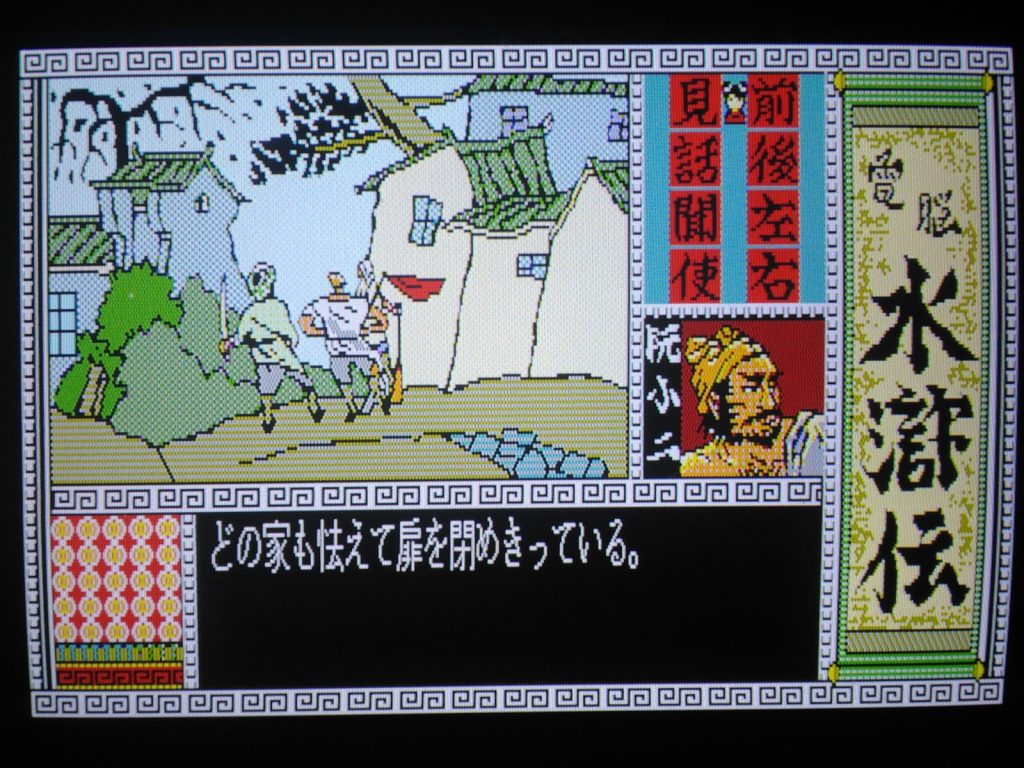

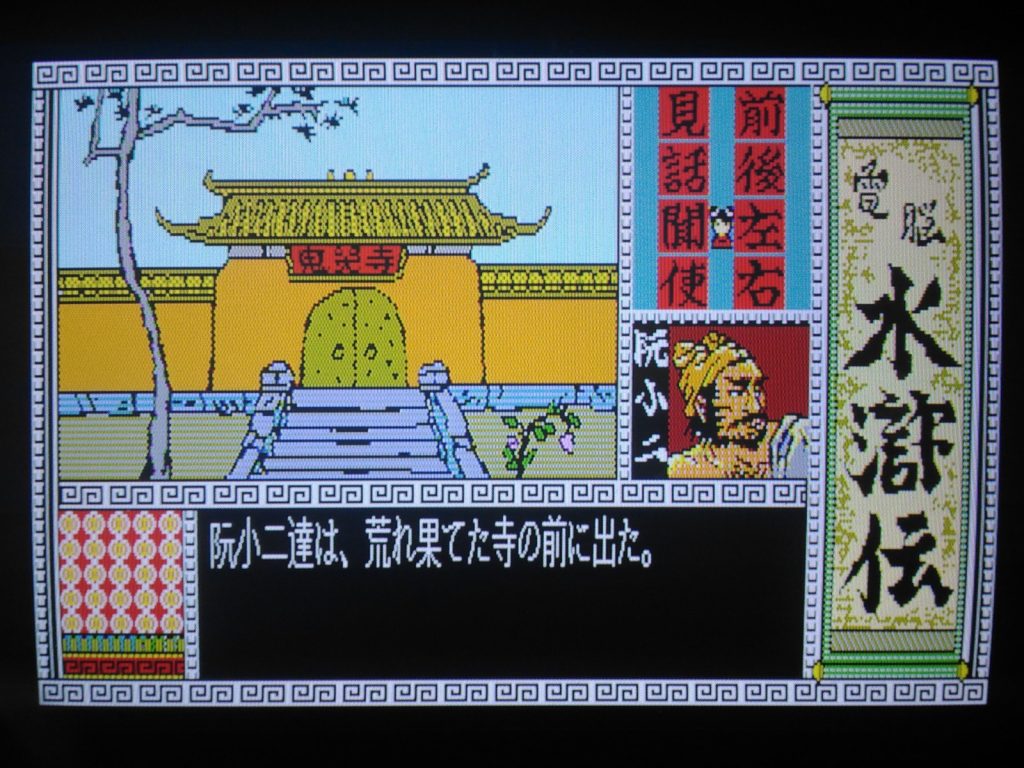

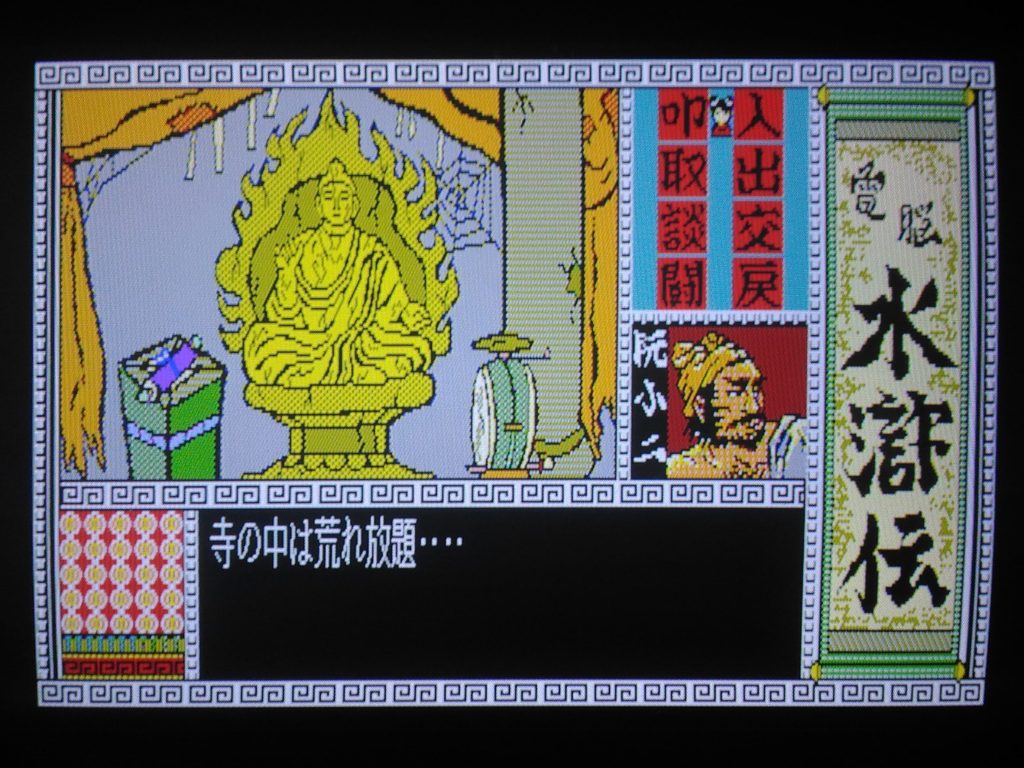

Denno Suikoden (graphic adventure based on classical Chinese literature)